2005 Dolan Media Samuel B. Spencer Journalism Awards – 1st Place Best Special Project

Check out Part II in the award-winning series:

The Fast and the Fraudulent

Insurance fraud and street-racers in Maryland

Part I

The Daily Record (Baltimore, MD)

November 18, 2005

Copyright 2005 Dolan Media Newswires All Rights Reserved

Section: NEWS

Length: 1830 words

Byline: Kathleen Johnston Jarboe

Not all street-racing boasts reveal insurance fraud. But after a few hours of searching, The Daily Record found one that did. One day last year as morning lurched toward noon, a kid code-named Str3ak logged on to a Web site for racers and typed a missive sure to impress:

"My friend Andy and I were ‘controlled skidding' at 10 m.p.h. with NO traction whatsoever … and ‘control-skidded' right into a curb," Str3ak wrote about his drive in the rain. "There, we looked at each other, got out, and calmly, ran our asses off, called the police and reported [the car] stolen. We got away with it, too."

Such admissions are rare. Chat board visitors spend much more time detailing race wins, car modifications and griping about how insurance "rapes" them.

But some insurance industry and law officials say the comment reflects an attitude endemic to parts of the street-racing community.

As racers struggle to pay for their cars, engine blow-outs, lost wagers and racing accidents, some turn insurance companies into personal piggy banks.

There is debate within the industry about how widespread the fraud is. But insurers started looking at the problem as infamous stories involving fraud and racing surfaced in California a few years ago.

Golden State law enforcement officials talk about a video tape found hidden in a kid's shoe during a roadblock stop. The self-made documentary shows racers speeding through town at more than 100 m.p.h. and fleeing an accident scene they caused. Later the friends talk about keying their car so they can report it as vandalized and get insurance money for new paint. The film shows one guy smashing the car window with a bat.

False police reports are a key part of the crime, according to investigators. If a racer bets car parts for a race and loses, sometimes he reports the parts he's given up as stolen. If he wants new rims, he can Photoshop the pricey hubcaps onto a picture of his car, submit a false theft report and get insurance money for the real purchase. A crash on the road or track can turn into a phantom hit-and-run claim. Policies rarely cover accidents if racing is involved.

Fraud aid

Sometimes racers receive assistance in their subterfuge.

In 2002, Santa Clara County in California, home of Silicon Valley, pioneered a sting to catch stores aiding racers in fraud. They sent an undercover police officer to about 50 body shops with an undamaged black Honda Civic and a proposition.

The officer wanted a new paint job. Already, he explained, he had reported the modified street-racing vehicle as vandalized. Now he just needed a shop estimate to give to the insurance company. If the estimate were below $3,000, the insurance firm wouldn't need to see the car to send him a check.

Nearly half the body shops bit, according to a Santa Clara County prosecutor. Some stores had been chosen with insider information. Others were picked at random. One store even offered to add his deductible to the estimate so the officer could get it back. The sting was quickly copied in other California jurisdictions.

"It sent shockwaves through the body-shop industry," said Stan Voyles, a deputy district attorney for Santa Clara County who worked with the case.

The extent of the crime is hard to estimate. Not all racers use fraud to fund their parts, cars and repairs. Many younger racers get money from wealthy parents. Others live at home or save and work on their cars, doing much of the work themselves.

In a Parkville performance shop last week, a damaged Nissan 240 SX sat parked inside. Car parts were scattered on the floor, shelves and walls. The Nissan's outer shell had a three-inch tear near the engine hood, which concealed a 400 horsepower engine. From the gas tank back, most of the body panel was missing, too. The auto had hit a wall during a legal drifting event — a racing sport that combines velocity with high-speed turns to create a showy display of smoke and skill.

Sponsors donated free body panels and tires to the vehicle. Brian Wilkerson, who owns the Mid Atlantic Motor Sport store, worked on the damaged auto.

"Good luck trying to find a place to give you a receipt for something you didn't buy from them," the 22-year-old Wilkerson said.

A Maryland problem?

Some industry officials say the crime is a California problem that hasn't reached Maryland. State insurance officials who investigate fraud allegations said they haven't seen any cases. Yet the Maryland Insurance Administration doesn't track whether false claims were related to street racing.

The agency doesn't need to know the perpetrator's motive. It just needs to prove there was insurance fraud, investigator Edward Henneman Sr. said.

A case Henneman worked this year involved a Pennsylvania man who reported his Corvette stolen while attending an Orioles game in Baltimore. Investigators double-checked the story when the man mentioned he rode the light rail to a stop that turned out not to exist.

They found the car had never left Pennsylvania. It had been in the shop because the engine had blown. He later swapped an engine from a second Corvette he owned into the first car.

"Did he blow the first Corvette street racing? I don't know. Is it insurance fraud? Yes," Henneman said.

Reactions from the local racing community vary. Some said they've never heard of the insurance scams. Others say it would be difficult to making a racing collision look like a normal traffic accident. But not all.

"It's not that hard," DJ said as he smoked a cigarette earlier this month. He didn't know anyone who had done it. But he had heard of the fraud.

The 22-year-old Maryland resident, whose last name was withheld because of potential insurance ramifications, has a deep bass voice. He stood near the finish line of the quarter mile race at Maryland International Raceway in St. Mary's County. As he spoke, souped-up cars thundered down the track.

"You know the right person, they print you up a receipt."

Speedy Clark runs the Clark Racing Chassis Inc. shop in Woodbine. He's been involved in the racing scene since he was a teen-ager. The 62-year-old says he's seen kids wreck their parents' sporty cars at the tracks. The local raceways allow all drivers to test their skill at the quarter mile.

Clark says such collisions often get claimed as freak parking lot accidents.

"What these insurance companies need to do is police what they insure much better and investigate the claims they get," Clark said.

Closer look

Auto and home insurance fraud cost the industry $30 billion a year, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau. The fraud can push insurance rates up for other customers. But determining what street-racing schemes cost the industry is difficult. Phony claims aren't unique to street racers. Even companies that began checking for racing connections haven't tallied the losses.

"It's hard to peel out street-racing fraud and come up with a dollar amount. … You got so many aspects of fraud involved in it," said Frank Scafidi, director of public affairs at NICB.

Adding to the difficulty in totaling a cost is the novelty of the situation.

"I'm not sure if most insurance companies have looked closely enough at the pattern of street racing claims to see that they may have a fraud problem," said James Quiggle, spokesman for the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud. "Insurance fraud is the hidden crime behind street racing.

"Still, investigators who began attending car shows, race tracks and illegal races noticed a trend. After writing down license plate numbers, it didn't take them long to find cars at these gatherings that had submitted questionable insurance claims.

At one event, a Geico investigator for the Washington region found 12 cars his company covered. Statistically, Geico should have paid an average of $8,000 a year to satisfy any claims from the vehicles. Instead, those 12 cars had cost the company $224,000.

"There was a scary disproportionate number of claims and size of claims by the people who were racing," said Joe Jackson, supervisor of the theft unit at Geico's Fredericksburg, Va. office.

The company went to more races, researched more customers and began canceling policies.

Jackson has a picture of a blue Mustang wrecked last year. The front fender and bumper are missing. The back end is smashed. Geico paid $29,000 in losses on the car's policy that had only brought in $1,100 in premiums.

The driver claimed he had hydroplaned in a single-car accident. The car had been equipped with a supercharger aimed to give it more power, and the owner had already purchased an identical car. When the company investigated the hydroplaning claim, it found it hadn't rained for five days surrounding the date of the crash. Geico denied the claim and reported it as fraud.

Insurance and law enforcement investigators say it is hard to prove auto insurance fraud. The individual cases don't garner much attention from prosecutors compared to larger scams. Also, it is hard to prove a negative — that something didn't happen.

Morality

Police officers say they need an undercover agent or a willing informant to catch insurance scams that involve stores and phony receipts. But street racers are loathe to turn on their associates. And, turning on others might mean implicating themselves.

According to a Baltimore County officer, there is a Charm City shop that gives drivers fake receipts for wheel rims. When the drivers come back with insurance money from the false theft report, the store then installs the decorative accessories that can cost over $6,000. The detective said the shop sometimes steals the rims back from its customers for an additional profit. But his unit hasn't been able to make the case without a sting and more informants.

"Within [the street racing] community, there isn't a sense of morality. There isn't a shock that this is really wrong," said Sgt. Bob Jagoe, a detective with the Baltimore Regional Auto Theft Team. "Most of them think that the big, bad insurance company is a multimillion-dollar pocket. … ‘I made all those payments over the years, never made a claim and I'm just getting what they stole from me back.'"

To some extent, the attitude carries over to cyberspace. Forum chatters often advise racers against telling their insurance carriers what they've done to make their car faster. Many insurers will drop or charge higher rates for customers who have souped up their car for speed.

Yet the groups have voices of reason, too.

Str3ak, the Internet chatter who bragged of insurance fraud last year, drew a quick rebuke.

"You weren't ‘controlled skidding' either. You were being dumbasses. And guess what? Everything you post here can be Googled by anyone," wrote a forum poster named WhoDriving? at www.streetracersonline.com."

I doubt you want to post people's names and any insurance fraud or false police reports you've submitted."

Next week, a look at the extent of the street-racing scene in Maryland and a budding effort by insurance representatives to push for tougher laws against the crime.

Part II in Street Car Fraud Series

The Need For Speed

The Price of Illegal Street Racing

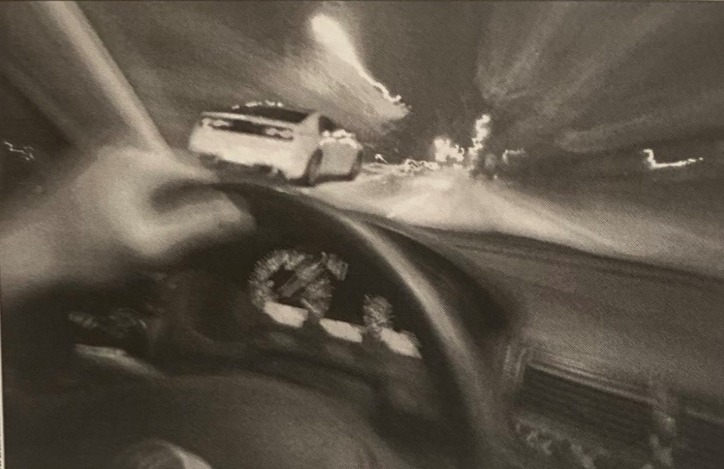

The stoplight was the flag. Red to green, and two cars catapulted down a Baltimore street earlier this month. Through the intersection. Down a quarter-mile straightaway. The roaring engines echoed off storefronts. Seven youths watched from a deserted parking lot. Regular midnight traffic trailed behind the racers. Then a silver Grand Prix pulled ahead of a Chevy Monte Carlo to win.

Money and bragging rights were at stake. A happy bettor from the crowd jumped up and down. "I want my money," the man shouted with his arms in the air. The Grand Prix pealed out as it re-entered the lot. Sometimes a local opportunist organizes the races, taking a cut of the bets.

Sometimes the police break up the scene. But there are other spots to street race in Baltimore. Places where one racer says nobody bothers them.

The Baltimore-Washington area and Philadelphia are home to some of the largest street-racing communities in the region, according to car enthusiasts. Baltimore, Rockville, Howard County and Fairfax County, Va., are quickly named as hot meeting spots.

Some insurers say the illegal scene has grown so much that it has become dangerous. But gauging the true extent of street racing is difficult. Official figures are lacking, and the racing community includes more than street racers. Some only modify their cars for show. Others limit racing to the track, where it is legal.

The Baltimore street where the Grand Prix raced is the stomping ground of a driver who preferred to be called Juice. The Daily Record withheld last names and some first names of racers in this series due to potential insurance ramifications.

Juice doesn't hold a regular job. Instead the 21-year-old Maryland resident turns the roads to gold.

His friend estimated Juice has won $70,000 on the streets. But Juice shied away from confirming the figure, as he waited to legally race at the Maryland International Raceway earlier this month.

Thousands attended the event in St. Mary's County. Motors revved in the background. Car clubs traveled together, setting up barbecues and folding chairs on the warm, sunny day. Only street-legal cars raced, and some hit speeds of 188 mph on the drag strip.

A barely dressed woman stretches around Juice's helmet. Juice races motorcycles and cars. His red Honda Civic doesn't look special with its faded red paint. But the vehicle sports an intercooler, turbo and nitrous oxide. The modifications and others turn it into a speedster that can hit a quarter-mile in under 12 seconds with the right tires.

The adrenaline rush attracts Juice to the scene. "It's always been a dream to drive fast cars and work on them," he said.

He's tinkered on dirt bikes and four-wheelers since he was a kid. He did most of the modifications on the car himself. And he has worked on friends' cars. He wants to open a performance shop one day and perhaps sell taped footage of his exploits.

But there is a fascination with the dangerous part of the sport, too. With what seems to be pride, he lists the crazy things he has seen while street racing: a car catching fire, pink-slip betting, accidents, murder.

The area around the New Carrollton Metro used to be the biggest street-racing spot in the area. Hundreds would gather each week to test their skills. It was here that Juice watched a mob turn on a racer who refused to pay up after he lost a race. The driver rammed into cars as he fled, angering more racers. They began shooting at the car as they pursued it. The next day Juice heard the racer was found dead.

It wasn't the only time he encountered death. During a street-bike race, he observed a car suddenly pull out into the racer's lane. Juice estimated the biker was doing 160 mph when it smacked into the vehicle. The biker died.

But Juice says such events aren't the norm. The illegal scene has evolved. Bettors have more mutual respect, and racers try to keep the wilder individuals away.

"Not everyone is like that. The street racing is not what really caused the accident. It's that they were not paying attention, were drinking or taking drugs," he said. "I've been out there a thousand times and never had an accident [like that]."

Juice's only wreck happened last year. His axle broke while racing, sending the car into a guard rail. He was fine, though the car was totaled.

But some collisions involving the illegal sport can be gruesome. Last year, 17-year-old Eric J. Kackley died when he lost control of his Toyota Celica while racing in Waldorf after 3 a.m. His opponent slowed before a turn in the road. But Kackley blasted forward, according to an officer that investigated the scene. The car hit the curb, flipped and ejected Kackley, who was not wearing a seat belt.

In Howard County last month, a Nissan Maxima tried to pass an Acura Legend on the right shoulder while competing on Route 216. Instead the Nissan lost control, struck the Acura, veered across the road into a ditch and overturned. An unbelted passenger was ejected from the vehicle. Police flew her to Shock Trauma. Alcohol had been involved, according to county police.

In June, 44-year-old Carlito R. Mandocdoc was hit by racers as he turned left into an Aspen Hill shopping center. A white Corolla first struck his car, causing it to spin. Then a second racer smashed into the vehicle."

[Mandocdoc] had no idea they were traveling as fast as they were," said Officer Derek Baliles, a spokesman for Montgomery County police. Law enforcement officials estimated the two young men were driving at least 30 mph over the speed limit.

Mandocdoc died. And the racers have been charged with manslaughter, among other things.

Tell-tale signs

Some insurers worry about the accidents, especially those who have begun to investigate the ties between the sport and collisions. After investigating such claims, Geico representatives began briefing state and other insurance officials across the country about the dangers of the sport.

"It's a small fraction of our book of business. But when they cause losses that are that exponential, and when they become such an obvious threat to public safety, as corporate citizens we had to become more involved," said Joe Jackson, supervisor of the theft unit at Geico's Fredericksburg, Va. office.

"Someone has to do something about it. We as a company weren't going to sit back and wait for someone else."

This year the insurer sent policyholders a tell-tale guide listing car modifications that might mean kids were racing. Several online chat rooms flamed the bulletin.

The night it was mailed, a group of racers visited the insurer's Tower Oaks office in Rockville. The group tried to damage security cameras. Then they spun around in their cars and pealed out of the parking lot.

"It was obvious that at least one of them must have been confronted by their parents," Jackson said.

Geico representatives said they plan to push for tougher laws against street racing in Maryland. The insurance officials point to a Florida law passed this year. The legislation increased penalties for participating in the illegal sport and allowed authorities to seize cars of racers caught more than once.

Yet judging the sport's prevalence can be difficult. Law enforcement officials from the state, city and several county departments said their jurisdictions hadn't had problems with street racing. But no units focus on the crime. And individual departments don't track the number of tickets issued for participating in a speed contest. The numbers must be accessed through the courts at the state level.

In fiscal year 2005, 485 tickets were issued across the state for racing. In 2002, the number was 657, according to the District Court Traffic Processing Center.

The numbers can be deceiving, according to some law officials. Racers might just as easily get an aggressive driving citation or a simple speeding ticket.

State accident reports yield even less information on the matter. The Maryland forms don't record if racing contributed to a collision. Knowing there is a connection often depends on personal recollections.

"I think there is a problem. But in terms of proving the problem, it's not as simple as looking at statistics," said Sgt. Bob Jagoe, who deals with street racing at times as a detective on the Baltimore Regional Auto Theft Team.

Jagoe said the illegal scene often goes undetected because it happens late at night. Racers wait until most have been asleep for hours to avoid traffic.

"Why would you have all these speed shops and nobody is racing?" Jagoe said.

The stores that modify cars can be hard to find in the yellow pages. But their names are advertised at racing events, on stickers of modified cars and on local chat forums. Justin's Performance Center in Glen Burnie, No Limit Inc. in Baltimore and Extreme Motorsports in Odenton are just a few.

Spending at such shops has skyrocketed in the past decade. In 1997, car enthusiasts spent $295 million on after-market parts for sport compact vehicles, some of the most commonly raced vehicles. By last year spending had grown to $4.1 billion.

"You can't even imagine how big it is," said a 22-year-old driver named DJ* about the local street scene. He said he and about 20 of his friends race every weekend.

Last week, as temperatures plummeted to 43 degrees and retail stores closed, close to 40 cars from the Autokrats car club gathered at a Best Buy parking lot in Columbia.

Two young men visiting from Cincinnati attended the meeting. They had asked around and searched on the Internet until they found a local club.

You would never get this many people out on a November night back home, said Brent, who declined to give his last name. Four cop cars dispersed the gathering. Still, about 20 cars drove a mile down the road and reconvened in an empty Krispy Kreme parking lot.

The meet offered car enthusiasts an opportunity to pop their hoods and show off their latest modifications. A black Honda Accord glowed blue from interior neon lighting. The car had aluminum floor plates to better reflect the lights under the dash. Its trunk had been replaced with molding to cover four large speakers. Car door lights danced to the stereo music.

"Some are for show. Some are for racing. Me? I'm for show," said Mark, a 25-year-old car enthusiast and Air Force service member scheduled for deployment to Iraq next year. He wore a silver necklace with a cross and an Old Navy sweatshirt.

He has spent $6,000 modifying the car. The Anne Arundel resident doesn't meet up with drivers often. He has a wife and two kids. But he's drawn to the culture and group discounts that come with membership in car clubs. His specialized exhaust should have cost $520. Mark paid $370 with the club discount, including shipping.

Part II

The Daily Record (Baltimore, MD)

November 25, 2005 Friday

Copyright 2005 Dolan Media Newswires All Rights Reserved

Section: NEWS

Length: 2163 words

Byline: Kathleen Johnston Jarboe

Alternative tracks

Not all street racing is organized with betting and finish lines. Some just race with friends. Others test each other informally on the highway, slowing down to about 40 mph, honking their horn and then speeding forward until there is a clear winner or a car in the way.

"Let's face it. Anyone who is a car fanatic is going to race at sometime or another," said Edward Henneman Sr., an investigator with the Maryland Insurance Administration.

The thrill of the illegal scene adds an edge to the neon, speed-inspired car culture. Mark estimates half of the Autokrats members compete on the roads.

Others keep racing at official courses. A 22-year-old performance shop owner said he used to street race but found the scene too much trouble. Traveling from parking lot to parking lot all night until cops showed up got boring. Then his car was stolen. He thinks street racers who saw the modified roadster at races swiped it.

Now Brian Wilkerson races Porsches and participates in legal drifting events — a racing sport that combines velocity with high-speed turns to create a showy display of smoke and skill..

"I'd rather race on a track where I can test the limits of my car," Wilkerson said, who runs Mid Atlantic Motor Sport in Parkville. He said he always felt he held back on the streets.

Official racing organizations try to encourage similar behavior. They've made a MTV show discouraging street racing and have worked with famous drag racers like Stephan Papadakis to spread the word about the dangers of illegal competition. The groups often say it is better to draw kids to official racing events than to hike penalties for street racing. Illegal racers say punishments like impounding cars are more likely to make them flee from cops.

Juice races at official courses but still takes it to the streets despite serving a few days in jail for his hobby. He searches for an explanation, when asked. In the end, it boils down to money and a speed addiction. It's impossible to set up bets at the track like on the roads. Plus the track has long lines.

"You pay so much money to race there, and you don't get to race as much as you should," he said.

* The Daily Record has withheld last names and some first names of racers in this series due to possible insurance ramifications.